November 21, 2025

Maria Sergeeva

Over the past decade, health systems across the world have poured resources into solving one of modern medicine’s most frustrating problems: fragmentation. The buzzword at the centre of these efforts is interoperability – the ability of different health information systems, devices, and applications to access, exchange, and cooperatively use data in a coordinated manner. The fundamental integration is crucial, but as we edge closer to this vision through national programmes like NHS England’s Single Patient Record, Germany’s electronic Patientenakte, and Australia’s My Health Record revamp, an uncomfortable truth demands attention: interoperability alone is not enough.

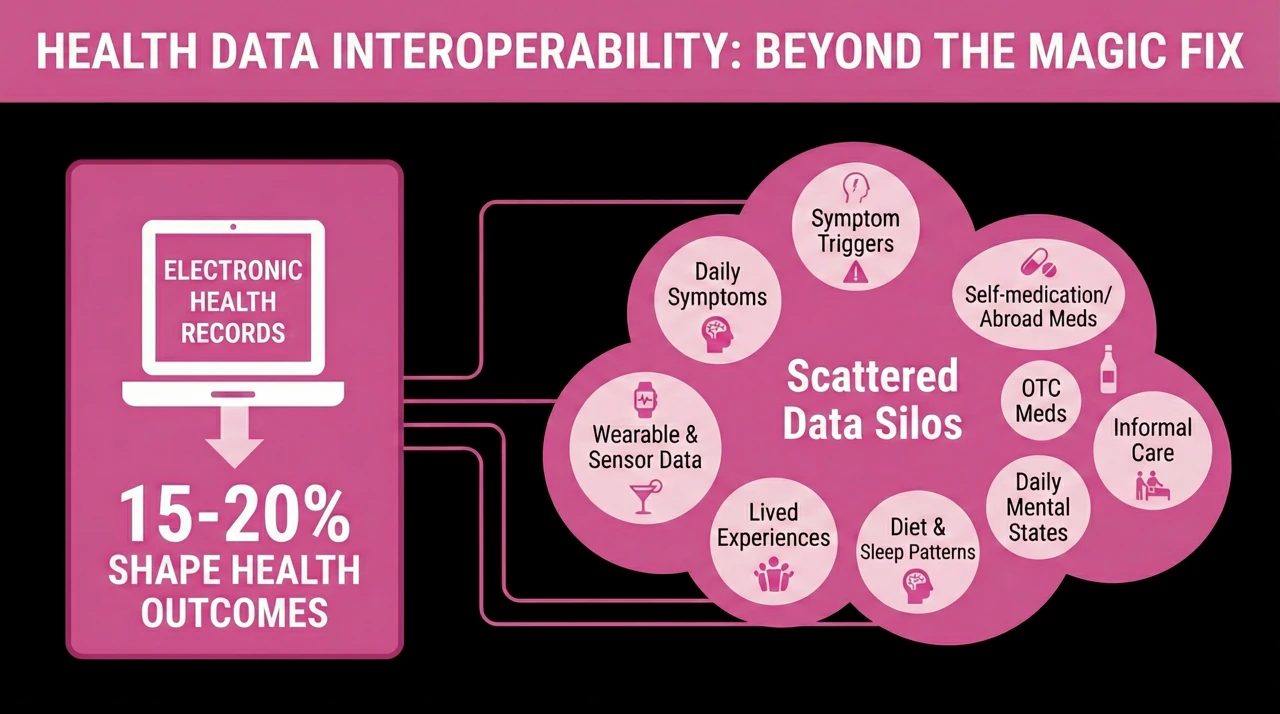

Without trying to minimise the importance of full interoperability, it’s often seen as a magical fix and an end goal. However, only 15–20% of the information that meaningfully shapes a person’s health outcomes lives in the electronic healthcare records. The rest lies scattered across silos that are far more diffuse and rarely recorded: daily symptoms, symptom triggers, personal baselines, over-the-counter meds, self-medication or medication from abroad not approved by the current country, alcohol, wearable and sensor data, diet and sleep patterns, lived experiences, informal care, and daily mental states. Most of this never reaches formal clinical channels.

A recent Korean clinical study found that 45% of patients failed to disclose significant past medical conditions or medication use during screening interviews – details that were later recovered through review of personal health records and self-reported data. In short: what’s missing from the chart can be clinically decisive.

The structural limitation of EHRs is that they are designed to document what happens within a health service, not around or beyond it. The most important evolution of care would mean stitching together the full, textured picture of a person’s health journey: clinical events, yes, but also the patterns, behaviours, and experiences that influence risk, compliance, resilience and recovery. This requires a shift in both mindset and infrastructure.

Finally, what we also need is not only systems that talk to each other, but systems that listen to people. Platforms that allow individuals to input, own and curate their own data – across formats, across time, across borders. Data sovereignty and personal control are not just ethical imperatives; they are functional necessities.

We need to move beyond the idea of the health record as something stored about you, to something built together with you. Such a record would not only support better care, but better self-understanding and thus self-awareness, motivation and responsibility. It would help people spot patterns, connect dots, and advocate for themselves in complex systems. It would enable continuity across moves, diagnoses, and life stages.

The future of health isn’t just interoperable. It’s personal, portable, and participatory. Let’s build accordingly.